Source: fibre2fashion

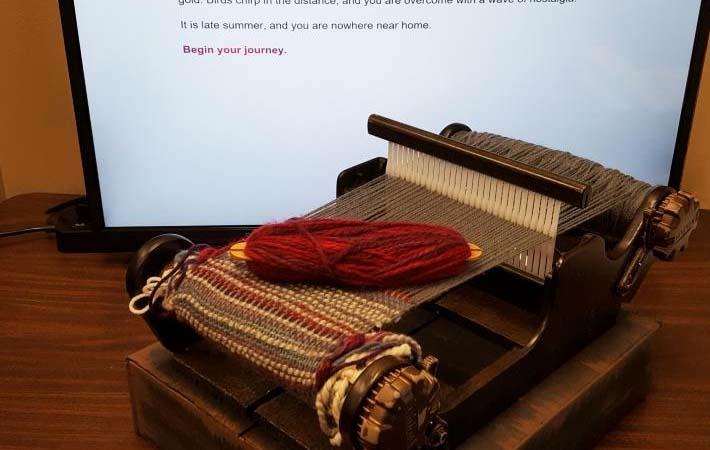

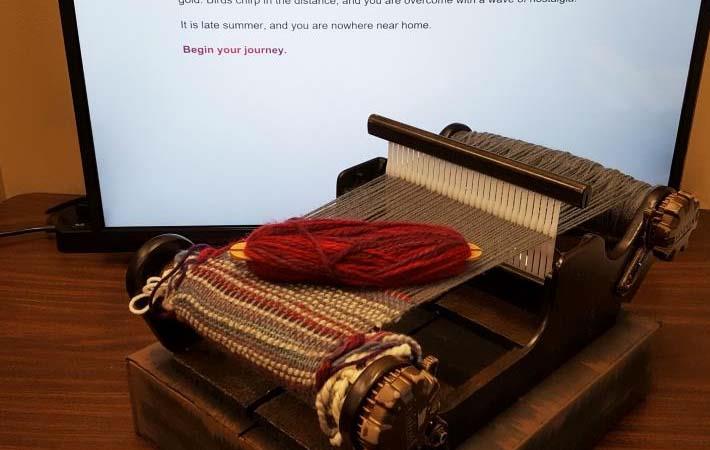

As computer capabilities evolve, new fabric-based interfaces are coming up. One version is a video game system called Loominary, which uses a tabletop loom as an interface to weave a scarf using a narrative videogame that follows the story of the Greek myths of Oedipus and Medusa (or a more child-friendly version with a story about a unicorn).

When most people think of interacting with computers, they think of traditional interfaces, like a computer mouse, keyboard, or cellphone. However, as computer capabilities evolve, so do the variety of interfaces. One intriguing and nontraditional idea is to use fabric-based interfaces for fun or to achieve a goal. Because all are familiar with fabric as a material, the systems also aim to be more inclusive.

In the system, the yarn is loaded onto sticks called shuttles to pass it through the loom, and a computer tracks the movement of these shuttles using radio frequency identification (RFID) devices and integrating them into the mechanics of the loom.

Josh McCoy, a digital media professor at the University of California–Davis and one of the minds behind the game, explained how they managed to track the correct yarn colours. “We ended up using an RFID and an RFID tab on the shuttle, the things with the yarn on them that you pull through the [loom] to thread another line. It’s the same technology that you use when you put your hotel card against the hotel door and it reads it and opens the door, the same type of tab,” McCoy said

The sensing equipment to allow a computer to read the movements of the RFID cards is hidden under the loom in a box. To figure out the technology McCoy had the help of Sarah Hendricks, who worked on how to track the weaving as part of her undergraduate capstone project.

McCoy came up with the idea for the loom along with Anne Sullivan, a digital media professor at the University of Central Florida whose background is in crafting. They wanted to leave users with a tangible product once completed. The duo also worked with master’s student Bri Williams write the story in a programme called Twine that allows users to create a branching story.

“When you beat a boss in a game, you have a unique story of how you got through it, and that tends to be what you kind of share with your friends. It's not the story about the game, it's what you did in the game,” Sullivan said. “The problem is that a lot of games don't capture that in any way, and so the inspiration for Loominary was … ‘How can we capture their story in a more tangible way?’ ” Sullivan said.

The makers hope that the game system will simultaneously appeal to both gamers who might be intrigued by the unusual interface and crafters who might not normally be attracted to video games. Crafting and computing have traditionally been viewed as disparate activities, but as Future Tense has explored before, one can easily inform the other. A movement known as computational crafting also blends the two disciplines.

Sullivan and McCoy hope that others will take the concept and develop it further. Loominary’s code and instructions are open source, which means that users can build their own versions, modifying the story as they desire. While both professors are interested in incorporating other crafts into future games, they also both plan to develop Loominary in different ways. McCoy wonders about the possibility of using artificial intelligence to generate a dynamic story each time rather than a static one, and Sullivan can also see incorporating other scarf references in pop culture into the gameplay.

While Loominary is unique, others have also experimented with fabric interface functions. Sean Ahlquist, an architecture professor at the University of Michigan, has created a large, flexible, fabric-based version of a touchscreen. Using an industrial-sized knitting machine, he makes large pieces of specially strengthened fabric that respond to the amount of pressure applied to them. It uses a combination of Microsoft Kinect software (which registers movement) and custom software that ties these changes in movement with changes in the fabric surface.